Ismail the Magnificent and the Loss of Liberty

Eihab Boraie delves into the life and times of Khedive Ismail who, with lofty ambitions and lavish spending, brought Egypt to its heyday, only to find himself and his country broke and in debt. Can parallels be drawn to modern day Egypt's rulers' costly dreams?

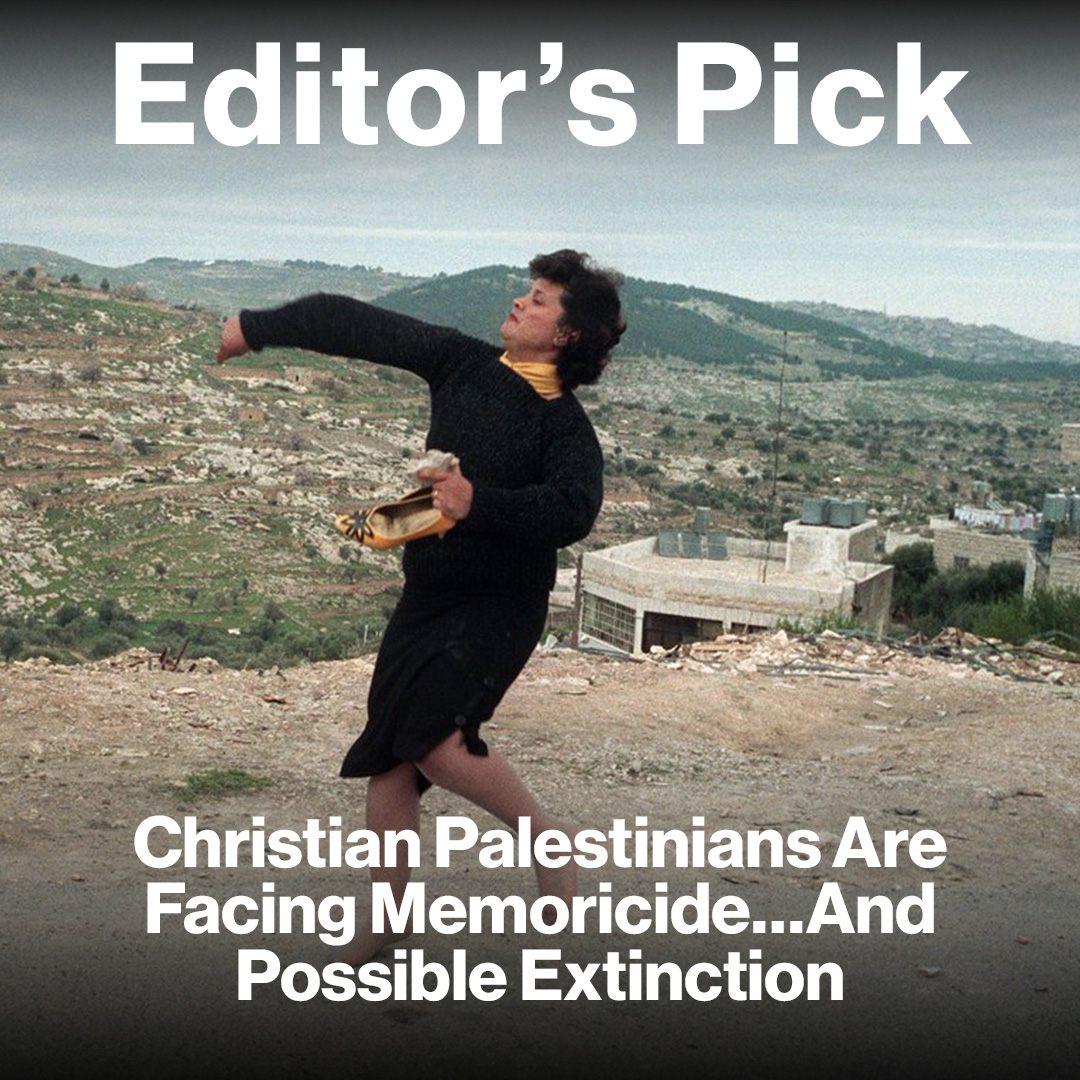

Egyptian history; the phrase conjures images of pharaohs and hieroglyphics, pyramids and ancient mysteries. However there are a myriad of interesting historic events and characters much closer to modern day Egypt. One such tale is that of Ismail the Magnificent, an Egyptian ruler in the era of the caliphs, who ambitiously attempted to build the ‘Paris of the Nile’, only to bankrupt a nation resulting in the loss of liberty.

Before cosmopolitan Cairo was destroyed by a century filled with wars, mismanagement, and religious extremism, it came close to sitting on top of the world as a beacon of liberty. Growing up in 1800s Egypt, a young Ismail Pasha was educated in France attending the Ecole d’etat-major in Paris where he was taught to embrace new ideas; he dreamed of implementing these ideas in his native Egypt, so that the nation could thrive and prosper. Upon completing his studies, Ismail stayed in Europe as an envoy representing Egypt in foreign courts. His duties involved meeting with important and influential figures, including Napoleon III, the Pope in Rome and the Sultan in Constantinople. Shortly after proving himself diplomatically, his uncle, Muhammed Said Pasha, entrusted his nephew with the command of 18,000 troops. Under his leadership, they were successful in quelling an uprising in Sudan. With his elder brother’s death due to a drowning accident, Ismail was named successor to his uncle and claimed the throne on January 19th, 1863, becoming the ruler of Egypt.

Once Ismail gained absolute power, he put forth his vision for a new Egypt, saying "My country is no longer in Africa; we are now part of Europe. It is therefore natural for us to abandon our former ways and to adopt a new system adapted to our social conditions." A man of action, Ismail Pasha began an unprecedented massive spending spree; he built institutions, infrastructure, palaces, and the Suez Canal. In 1867, the Ottoman Sultan finally recognised Ismail Pasha as Khedive of Egypt, and authorised a change in the rules of succession to allow the throne pass from father to son rather than brother to brother.

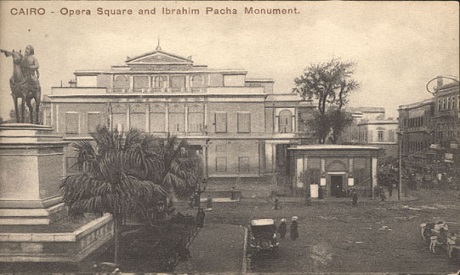

Ismail’s rule spanned 16 years (just over half of Mubarak’s rule) and yet he was able to leave a legacy that boasted a plethora of impressive projects. According to author of The Mena House Treasury Andreas Augustin: “Under his rule, 5,000 schools were built, railway and irrigation canals largely expanded, a parliament was created and laws on the Napoleonic model codified.” Also built under his rule were the Giza Zoo, The Cairo Opera House, The Mena House and Zamalek's The Gezirah Club; not to mention an attempted crackdown on slavery.

Although the Suez Canal project wasn’t initiated by the Khedive Ismail, its completion came under his watch. In 1869, he inaugurated the canal by inviting world leaders to a lavish and costly ceremony to mark the occasion. “At the festivities, all the powers of Europe were officially represented […]. Even England forgot her old political jealousy, and was adequately represented. In order to impress his royal guests, Ismail attempted to turn this unique oriental city into a feeble copy of a third rate European capital. Parks and public gardens were planted, palaces restored, and boulevards built, and gas was laid in chief streets,” writes Eustace A. Reynolds-Ball in The City of The Caliphs, adding that “Even a new opera was “commanded” for the occasion, Verdi composing the Egyptian opera “Aida” to entertain the Khedive’s guests. It has been computed that expenses attendant on the inauguration of the Suez Canal cost the Khedive, or rather Egypt, over four million sterling; and, no doubt, this lavish expenditure materially contributed to bring about Ismail’s financial collapse and virtual bankruptcy a few years later.”

Commissioning of a new opera to commemorate the opening of the canal is just one example of the Khedive’s lavish spending and bravado. Aida is considered one of the most important works of European Opera, however its debut is disputed, as initially composer Giuseppe Verdi refused to write a hymn for the opening ceremony of the canal saying “I do not compose occasional pieces!” Despite his apprehension, Verdi was offered 150,000 Francs and agreed to compose the piece, but its Cairo debut wouldn’t be held until Christmas Eve of 1871. The performance was so mesmerising that “it became one of the most treasured memories of a winter on the Nile for generations of travellers to come,” writes Augustin.

It seemed that anything Khedive Ismail wanted, he bought, never thinking of the consequences. In 1869, after French sculptor Frédéric Bartholdi presented Khedive Ismail with a miniature Statue of Liberty. The instantly enamored Khedive commissioned a giant replica of the statue, asking that the words “Egypt the Beacon of Asia” be placed on the pedestal at the entrance of the Suez Canal

The only changes Bartholdi suggested from the yet-to-be-built Statue of Liberty in New York, was that the woman be darker, and that she would holding a jar in lieu of a torch. Though it may seem a strange choice, the jar was meant to symbolise an important aspect of Egyptian history; the Pharaohs developed jars to store honey, olives, and just about anything else, allowing them to thrive and build their great civilisation.

Bartholdi returned to France to build the statue that was scheduled to be inaugurated on November 16, 1870. However, that never happened as Khedive Ismail had a rude awakening to his big spending ways; he couldn’t afford to pay the $600,000 demanded for its creation, a price which paled in comparison to the cost the French put into its design and construction. It is believed that the project cost about $2.25 million. Instead of ditching the project, Bartholdi decided to give the statue to United States in exchange for building the pedestal and accessories. Shipped out in 350 pieces, the Statue of Liberty was assembled and then inaugurated on October 28, 1886, by President Grover Cleveland.

Khedive Ismail established himself as a magnificent diplomat and visionary; but he was unfortunately a terrible economist and military commander. The skyrocketing value of Egyptian cotton (thanks in part to demand created by the American Civil War) fueled the Khedive’s perception of Egypt’s immense (but non-existent) wealth. Almost overnight, the Egyptian crop valued at five million English pounds became worth 25 million annually. With the Suez Canal bringing in a new revenue stream, Egypt seemed poised to become a financial super power, and yet failed to keep their books balanced thanks to a variety of ambitious projects and a costly war with Ethiopia.

Towards the end of his rule, Khedive Ismail was forced to sell his roughly $4 million stake in the Suez Canal to foreign investors to pay some off the country's debt. Under his reign the, national debt ballooned to over £100 million sterling (as opposed to three million when he acceded to the throne), failing to understand the fundamental idea of liquidating his borrowings to borrow at increased interest was a bad idea. “Ismail failed for lack of patience and judgement. He tried to rush his transformation scene. He wanted by a stroke of the pen, to turn the most conservative people on earth into a living embodiment of all the virtues of a progressive and enlightened civilisation. He had no patience for the slow conversion of a nation almost as stolid and immovable as their own Pyramids,” writes Reynolds-ball. His reckless spending resulted in Great Britain and France having the Ottoman Sultan deposing Ismail in 1879 in favour of his son Tewfik Pasha, which paved the way for the British occupation three years later. This marked the turning point of monarch rule, as many Egyptians looked at his prodigy as a puppet for foreign interests not to be trusted, eventually overthrowing his grandson King Farouk in a military coup decades later. As for Khedive Ismail, some believe he passed away in exile, while others claim he died attempting to guzzle two champagne bottles at the same time. The latter seems like a more fitting end for a man who couldn’t help but treat himself.

The more one reads about the Khedive Ismail the more they realise that comparisons can be drawn to Egypt’s current ruler. Building a Suez Canal, arguments with Ethiopia, and dreams of expensive new cities, all seem to be part of President Sisi’s vision. If history proves to repeat itself we may find ourselves once again in the position where foreign interest dictate Egyptian policies thanks to our historic inability to understand economics and paying its cost with Egyptian liberties.

- Previous Article Dr.Sisilove or How (Not) To Diffuse A Bomb

- Next Article Another Exam Leaked in Egypt

Trending This Week

-

Apr 23, 2024

-

Apr 18, 2024