The Nakba Has Been Erased From Historical Archives. What’s Next?

The “truth” is there, but you can’t Google it anymore, it changes by the second now.

The “truth” is out there, but you can’t ‘look it up’ anymore, it changes by the second now.

Today, you can’t Google ‘when was…’ without ‘the state of Israel established?’ preceding ‘Palestine founded?’. If our current events are subject to rapid alterations mere hours after they occur, what certainties can we hold regarding the integrity of historical archives? If colonisers are disposing of any self-vindicating evidence, how can those who’ve suffered under their tyrannical occupation tell their “truth”? These questions are not hypothetical. In reality, after nearly eight decades of systematic erasure, Palestinians have been compelled to assume the roles of their own journalists, archivists, activists, and storytellers. Having no control over the way their history is being documented, they had only literature, art, and film to preserve their narratives, or at least that's what they, and we, naively believed.

The reality is as such: those who wield the persuasive power of narrative ultimately control what is consumed.

In this context, the term ‘narrative’ encompasses more than the written word; it involves the articulation of false histories to exploit ignorance, and the deliberate censorship of work intended to reveal the harsh realities of the Palestinian plight. The words "immoral," "responsible teaching," and "guarding people's minds" are tossed about frivolously, seemingly to absolve those perpetuating the erasure of guilt associated with withholding the “truth”.

To the unassuming individual, the concept of 'banned art, film, literature and files' is prevalent in most countries around the world. However, the issue of Palestinian censorship is far more insidious than merely removing chapters or censoring scenes. This subject traces back to a deliberate mission to erase the Nakba from historical archives.

The term 'Nakba,' meaning 'catastrophe' in Arabic, symbolises the extensive displacement and dispossession of Palestinians during the 1948 “Arab-Israeli” war. Before the Nakba, Palestine was a diverse and multicultural society. However, tensions between Arabs and Jews intensified in the 1930s, driven by a surge in Jewish immigration due to European persecution and the Zionist movement's aim to establish a Jewish state in Palestine.

In November 1947, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution partitioning Palestine into two states, one for Jews and one for Arabs, with Jerusalem under UN administration. The Arab world rejected this plan, deeming it unjust and in violation of the UN Charter. Jewish militias initiated attacks on Palestinian villages, leading to the displacement of thousands. The situation evolved into a full-fledged war in 1948, coinciding with the termination of the British Mandate, the withdrawal of British forces, the declaration of Israel's statehood, and the intervention of neighbouring Arab armies. Israeli forces launched a significant offensive, resulting in the enduring displacement of over half of the Palestinian population.

In an academic paper titled ‘The Erasure of the Nakba in Israel’s Archives’, UCL’s Jewish Studies scholar, Seth Anziska, states: “While methods of depopulation have long been discussed and written about by scholars drawing on oral history sources and a variety of primary material - including work published in this journal - many historians and every Israeli government since 1948 have routinely denied Israeli agency in the making of the refugee population. The battle over responsibility for the 1948 Nakba thus remains at the heart of a reckoning with the genesis of Israel’s birth and Palestinian statelessness, and it includes questions of intentionality, moral and financial responsibility, as well as which voices get to narrate the tragedy of displacement itself.”

The validity of documentation regarding files pertaining to the 1948 Nakba has constantly been questioned by Palestinian and Israeli scholars, with willful erasure and destruction tactics confirmed as vicious and pernicious attempts to rid the past of violent Zionist actions. Israeli scholar Benny Morris sought out to question the rampant expulsion of Palestinians, referencing a version of the ‘migration report’ in a 1986 article that relied on archival material dating back to 1948.

“Morris clarified Israeli culpability in expelling Palestinians, and preventing the return of those who fled, while also shedding invaluable light on atrocities and war crimes committed by Israeli forces. Yet in an Orwellian act of self-censorship that began in the early 2000s, the Defense Ministry’s secretive security department, Malmab, spearheaded efforts to reclassify documents and methodically remove files from various archives across Israel to hide evidence of Israeli responsibility for the Nakba.”

Those seeking the “truth” do not need to look far to find it. The people who have torn apart documents and set history ablaze with their own hands have publicly - and proudly - addressed their acts.

In an article published in Israeli newspaper, Haaretz, titled ‘Burying the Nakba: How Israel Systematically Hides Evidence of 1948 Expulsion of Arabs’, Yehiel Horev - the head of the Defense Ministry’s security department from 1986 to 2007 - is questioned about his role in Malmab’s mission to clear documents that “might damage Israel’s image.”

But isn’t concealing documents based on footnotes in books an attempt to lock the barn door after the horses have bolted?

“[...] If someone writes that the horse is black, if the horse isn’t outside the barn, you can’t prove that it’s really black.”

This type of violent erasure continually haunts Palestinian refugees, leaving them perpetually unable to employ public discourse and documentation to substantiate their dispossession. They’re left to resort to what remains of their physical possessions whilst their eyewitness testimonies are forcefully altered and denounced.

In Anziska’s own words: “For decades, survivors of the Nakba sought to tell others about what they experienced and the nature of their dispossession: in photographs and interviews, poetry and art, historical writing and a variety of memorial practices. Yet the eyewitnesses to and survivors of the 1948 tragedy were often discredited, their reliability undermined, and the veracity of their recollections called into question. In the case of Palestine, the danger that fetishising documents gives succour to the victor’s version of history has particular resonance. The limits of the New Historians and revelations within the Israeli archives are perfectly clear: there must be a broad range of narrators delving into the Palestinian (and Zionist) past.”

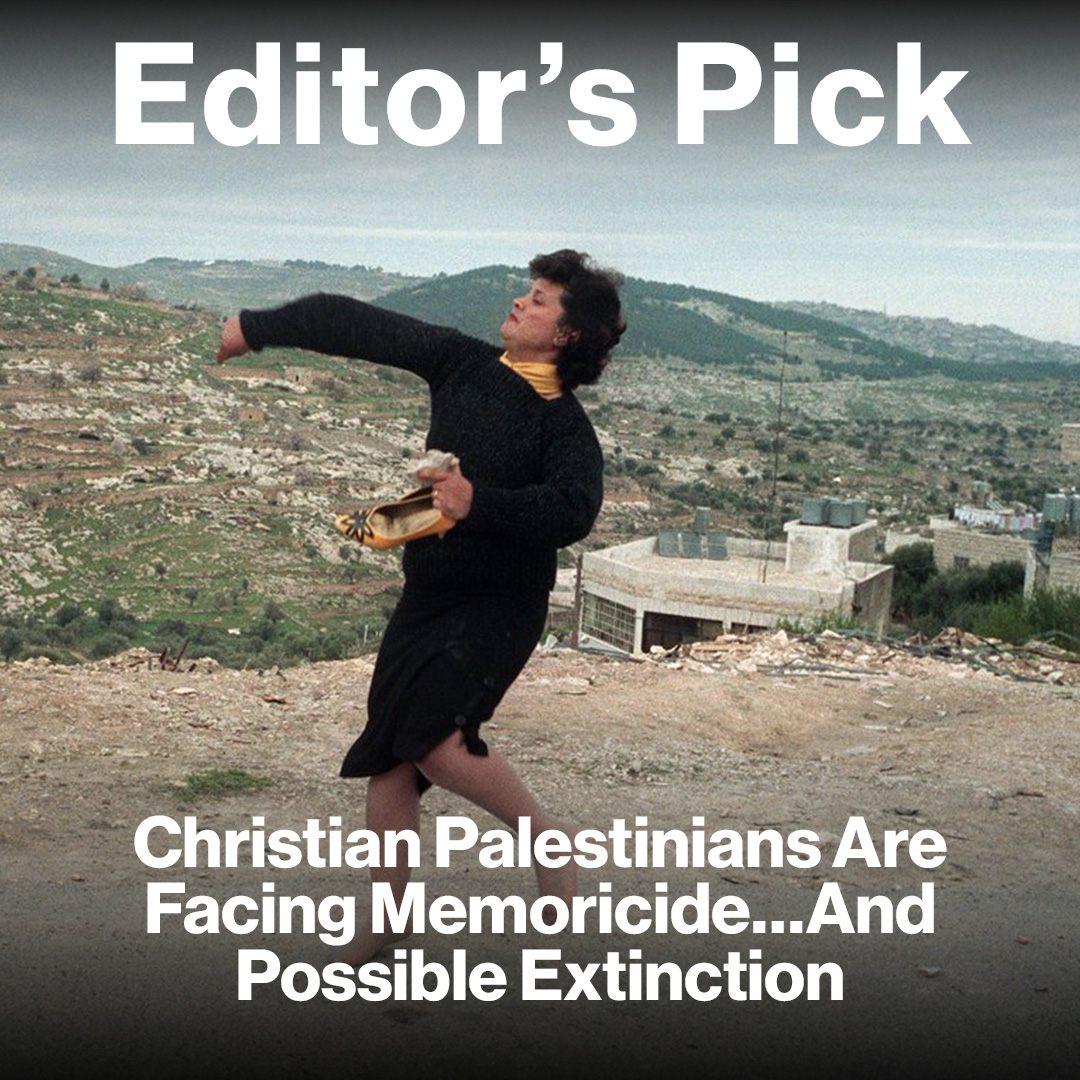

However, to claim this issue as a Zionist past is a grave generalisation, for the Zionist mission to erase and censor the Palestinian plight has never once withered. To this day, Palestinian stories in literature, art, and film are deliberately removed from circulation to ensure that the fabricated narratives being propagated by Zionists remain impervious to formal debunking. The mere presence of the word ‘Palestine’ has ultimately gone to send shivers down publishers’ spines, for it reeks too much of the “truth” to be consumed by those they’ve - forcefully or otherwise - tube fed fallacies.

In a guest post made to the School Library Journal in 2022, author Nora Lester Murad, delineates the realities of attempting to publish works on the Palestinian struggle for freedom, even in self-dubbed ‘democratic’ states across the US. “Palestinians aren’t on the radar of most advocates for marginalised books,” she explains. “What I’m finding in my research about censorship of Palestinians is concerning. Although advocates of intellectual freedom, freedom to teach and the right to learn stand up (appropriately so!) for books about Black and brown communities, the intense, multilayered censorship of Palestinians goes virtually unchallenged – and, in fact, unnoticed. Simply put, Palestinians and their literature are invisible to organisations like the American Library Association, National Coalition Against Censorship, and the National Council of Teachers of English, among others.”

This was the most tame observation made thus far by Palestinian authors, others were met with pure hostility and blatant rejection. Weaponized claims of anti-semitism at the mere utterance of Palestine resulted in a legal battle and a series of violent threats for Golbarg Bashi, the Iranian-American author behind children’s book ‘P is for Palestine’. The independently published alphabet book was protested against across the US. Zionist communities in Illinois’ Highland Park, condemning the book for equating the letter “I” with “Intifada”, and claiming it a violent form of resistance that children must never learn of.

A case breakdown published on Palestine Legal - an organisation that “protects the civil and constitutional rights of people in the U.S. who speak out for Palestinian freedom,” further delineates the extent of the censorship Bashi witnessed and continues to grapple with, “The author, Golbarg Bashi, received messages threatening to report her to the Department of Homeland Security and deport her to Guantanamo, along with p*rn*graphic messages and calls for her book to be banned or burned. Police were also alerted in advance of the author’s book signing after she received death threats [...] Israel advocates complained about the use of the word “Palestine” in the book’s title. The Stephen Wise Free Synagogue also opposed the use of the word intifada to illustrate the letter I, threatening to ban Book Culture from a book fair if it did not denounce the book.”

What happened to Bashi’s ‘P is for Palestine’ is not an isolated incident. It must be understood within the broader context of the deliberate erasure of Palestinian voices, memories, and their historical narrative. The Nakba’s documentation and Palestinian literature were not the sole victims. This predatory quest to hunt and neuter works that portray Israel’s culpability in the deletion of Palestine also arose in response to director Mohammed Bakri’s 2002 documentary, ‘Jenin, Jenin’. The lawsuit in question followed allegations made by Nissim Magnaji - the Israeli soldier whose actions were portrayed in the documentary - implying the ‘film’ stole money from an elderly Palestinian man. The ruling then conveniently veered from the original investigation - regarding the alleged theft - by stating that Magnaji had been “sent to defend his country and found himself accused of a crime he did not commit”.

The same crimes that were composed of - as stated by the Human Rights Watch (HRW) - “severe human rights violations, including unlawful killings, disproportionate use of force, arbitrary arrests and denying access to medical treatment.”? The same crimes that are being perpetuated against babies, merely months old and at times unborn, at this precise moment in time?

Bakri’s silenced voice echoed far louder than the words he was no longer permitted to utter. In response to documentary’s banning, Bakri confided in a few media outlets regarding the reality of the situation at hand, In an interview with the New Arab, Bakri explains, “I will not apologise for what I did … [the film] was attacked ferociously by the Israeli media.” Bakri’s lawyer also questioned the ruling, describing it as a “political decision” aimed at “silencing any voice that differs from the Israeli narrative”. Whilst unsaid, the director’s statement is a testament to the Israeli fear of letting the “truth” run its course.

Today, the violence persists. As the perpetual genocide of the Palestinian people continues eroding and devouring what is left of the population, the world’s reactions, once again, proved the extent of its apathy. Why bite the hand that feeds you? Isn’t that how the “expression” goes? Amidst a heart wrenching outcry for a humanity that now seems to be buried beneath the same Gazan rubbles, certain stances by global institutions have, again, proved that ‘if you can’t capitalise on the struggles of the oppressed then they no longer serve you’. A ceremony scheduled by the Frankfurt Book Fair to celebrate and award Palestinian author, Adania Shibli, was cancelled soon after the October 7th “attack” on Israel. The award Shibli was intended to receive was in acknowledgement of her novel ‘Minor Detail’, a harrowing real-life account of the rape and murder of a Bedouin girl by an Israeli army unit in 1949 with the fictional narrative of a female journalist investigating the crime in the Palestinian city of Ramallah, decades later. But alas, you can’t advocate for a narrative that might re-ignite memories of a pre-October 7th Palestine, can you?

If the circumstances are undeniably in your favour, if you are genuinely a victim of targeting, abuse, erasure, and violence, why must you expend relentless efforts to reshape a history that you are firmly positive is honest? If you staunchly believe that everything you assert is the absolute “truth,” is impeccable, why do Palestinian archives, literature, and film pose such a deeply unsettling threat to your existence?

- Previous Article سندباد الورد أضحي سلطاناً: مراجعة لألبوم شب جديد والناظر 'سلطان'

- Next Article Egyptian Embassies Around the World

Trending This Week

-

May 13, 2024

-

May 14, 2024