How Egyptian Architect Waleed Arafa Designed His Modern Cairo Home

Nominated for the Aga Khan and Hassan Fathy awards, the architect’s house was a groundbreaking statement of design and culture.

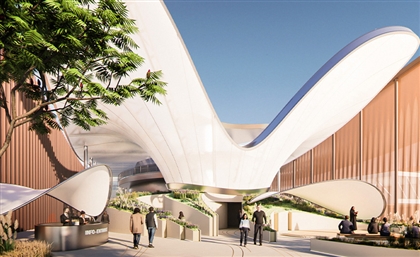

The world of design and architecture was brought to a halt when Dar Arafa Architecture built the Basuna Mosque in Sohag, a truly contemporary Egyptian architectural statement that was celebrated globally. While the occasion earned them accolades, it wasn’t the Cairo-based firm’s groundbreaking moment. Founder Waleed Arafa - an award-winning Egyptian architect and an acclaimed researcher of Islamic art and architecture - built his house in New Cairo in 2006. Aptly named ‘Dar Arafa’, the house was nominated for both the Aga Khan Award for Architecture and the Hassan Fathy Award due to its design novelty.

Located on the eastern outskirts of Cairo, its land was procured in a newly developed area as a response to an increasing need for space and greenery. “As a family, we were starting to outgrow our home in Nasr City,” Arafa tells SceneHome. “We had a sizable collection of books to reshelf and we wanted an open space in which to entertain and host our cultural salon.”

Located on the eastern outskirts of Cairo, its land was procured in a newly developed area as a response to an increasing need for space and greenery. “As a family, we were starting to outgrow our home in Nasr City,” Arafa tells SceneHome. “We had a sizable collection of books to reshelf and we wanted an open space in which to entertain and host our cultural salon.”

“My father couldn’t imagine living without a green area where he could practise his holy rites of gardening,” Arafa recalls. Fatima Mahfouz, Arafa’s mother and an agricultural engineer by education, was also an avid lover of greenery, reading and haberdashery. “She was in dire need of her own hermetic space to seek refuge when the extroverted life of her husband became too much.”

“My father couldn’t imagine living without a green area where he could practise his holy rites of gardening,” Arafa recalls. Fatima Mahfouz, Arafa’s mother and an agricultural engineer by education, was also an avid lover of greenery, reading and haberdashery. “She was in dire need of her own hermetic space to seek refuge when the extroverted life of her husband became too much.”

The homeowners insisted on a design that would, in addition to their own spacious private unit, offer extra units as potential residences for any of their six children once they decided to form their own families. A flexible scheme that balanced privacy and hospitality was the key element required in addressing all of their needs.

The homeowners insisted on a design that would, in addition to their own spacious private unit, offer extra units as potential residences for any of their six children once they decided to form their own families. A flexible scheme that balanced privacy and hospitality was the key element required in addressing all of their needs.

“The house was organised around a tree scheme, the trunk being the main unit that enjoyed exclusive access to the 203 sqm private garden,” Arafa explains. “The branches, so to speak, were none but the three 200 sqm units reserved for new additions to the family.”

“The house was organised around a tree scheme, the trunk being the main unit that enjoyed exclusive access to the 203 sqm private garden,” Arafa explains. “The branches, so to speak, were none but the three 200 sqm units reserved for new additions to the family.”

The design capitalised on the ‘zero level’ of the house being 3.60 to 4.20 metres higher than that of the neighbouring house in the back. This enabled what was deemed to be a “poorly ventilated, under lit and uninhabitable basement” into a comfortably luminous and atrium-like space overlooking a spacious garden.

The design capitalised on the ‘zero level’ of the house being 3.60 to 4.20 metres higher than that of the neighbouring house in the back. This enabled what was deemed to be a “poorly ventilated, under lit and uninhabitable basement” into a comfortably luminous and atrium-like space overlooking a spacious garden.

Boundaries of the first two levels were shrunk back due to the aforementioned extra flooring, allowing for the garden to sit comfortably and enabling a courtyard to exist within a new configuration. The resulting main unit gives the residents an airy, double-height space where they simultaneously engage in both their books and garden that seamlessly blend into each other through the transparent divide of curtain walling.

Boundaries of the first two levels were shrunk back due to the aforementioned extra flooring, allowing for the garden to sit comfortably and enabling a courtyard to exist within a new configuration. The resulting main unit gives the residents an airy, double-height space where they simultaneously engage in both their books and garden that seamlessly blend into each other through the transparent divide of curtain walling.

“The building regulation, allowing neighbouring buildings to build as close as six metres from Dar Arafa on both longitudinal sides and eight metres from the rear, forced the building to search for views within its own boundaries,” Arafa explains, as his house stands out amidst New Cairo architecture.

“The building regulation, allowing neighbouring buildings to build as close as six metres from Dar Arafa on both longitudinal sides and eight metres from the rear, forced the building to search for views within its own boundaries,” Arafa explains, as his house stands out amidst New Cairo architecture.

Instead of being muffled by high walls in the rear area, the architect intended on cladding the walls in white planes of marble. “Designed to receive water, which will in turn benefit the garden irrigation system, the wall is equipped for natural foliage and wildlife, turning this potentially restraining high wall into a perpetually beautiful tableaux of natural life,” Arafa explains.

Instead of being muffled by high walls in the rear area, the architect intended on cladding the walls in white planes of marble. “Designed to receive water, which will in turn benefit the garden irrigation system, the wall is equipped for natural foliage and wildlife, turning this potentially restraining high wall into a perpetually beautiful tableaux of natural life,” Arafa explains.

Arafa’s ingenious approach to building his ‘dar’ left no stone unturned, which includes analysing the soil found on site before deciding on the structural configuration and tailoring of materials that would erect the house. “The type of soil was suitable for producing concrete. This presented a chance to reduce costs and environmental impact,” he recalls.

Arafa’s ingenious approach to building his ‘dar’ left no stone unturned, which includes analysing the soil found on site before deciding on the structural configuration and tailoring of materials that would erect the house. “The type of soil was suitable for producing concrete. This presented a chance to reduce costs and environmental impact,” he recalls.

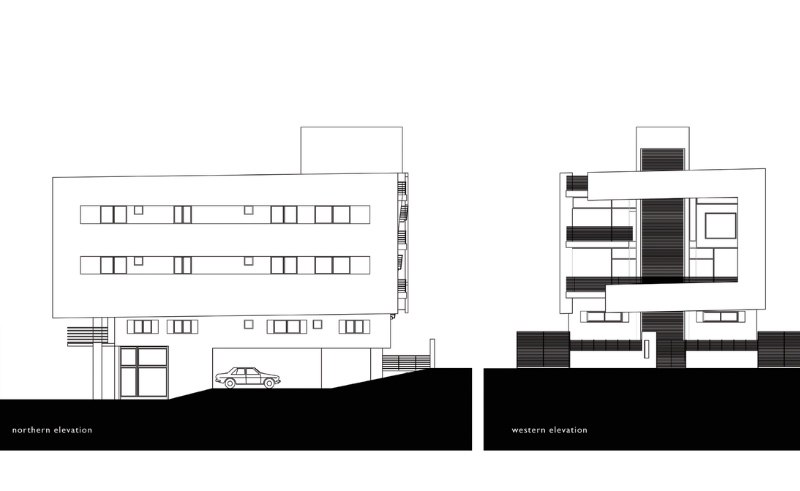

The main structure is made of reinforced concrete and light hollow blocks. It consists of 19 concrete columns and four hollow block slabs with the widest spanning 8.23m. The top three slabs extend and cantilever in all directions to assume the maximum permissible built-area: 0.6m on both sides, 2.25m on the main facade and 2.75m by 14m wide on the rear.

The main structure is made of reinforced concrete and light hollow blocks. It consists of 19 concrete columns and four hollow block slabs with the widest spanning 8.23m. The top three slabs extend and cantilever in all directions to assume the maximum permissible built-area: 0.6m on both sides, 2.25m on the main facade and 2.75m by 14m wide on the rear.

Locally-produced and light-weight, the sand-lime bricks were used to construct cavity walls in the exterior and in-between units, as well as constructing the internal partitions. “The usage of such bricks offered many advantages environmentally, structurally and economically, as well as in terms of health and safety. In addition to its excellent thermal and sound insulation properties, this sand-lime brick is fire resistant,” he says, referring to the material’s ability of withstanding 860 degrees Celsius for three hours. “It effectively reduces the amounts of reinforced concrete required if the heavier, conventional red bricks were used. Hence, decreasing mechanical loads and seismic stress.”

Locally-produced and light-weight, the sand-lime bricks were used to construct cavity walls in the exterior and in-between units, as well as constructing the internal partitions. “The usage of such bricks offered many advantages environmentally, structurally and economically, as well as in terms of health and safety. In addition to its excellent thermal and sound insulation properties, this sand-lime brick is fire resistant,” he says, referring to the material’s ability of withstanding 860 degrees Celsius for three hours. “It effectively reduces the amounts of reinforced concrete required if the heavier, conventional red bricks were used. Hence, decreasing mechanical loads and seismic stress.”

After the components of the building's skeleton were settled, it was time for the facade to get its fair share of the architect’s thoroughness. The result was a facade that’s ahead of its time and presents the house as an example of modern architecture that is informed by tradition, heritage and knowledge.

After the components of the building's skeleton were settled, it was time for the facade to get its fair share of the architect’s thoroughness. The result was a facade that’s ahead of its time and presents the house as an example of modern architecture that is informed by tradition, heritage and knowledge.

“Sandy desert winds and a merciless sun are probably the fiercest enemies of any facade in Egypt,” Arafa admits. His response was, well, “if you can’t beat them, join them.” A local type of sandstone known in Egypt as ‘Hashma’ was custom-cut for the house. The stone’s thickness, combined with 30cm cavity walls and its natural properties helped increase the time-lag, subsequently improving thermal insulation. Aside from the functionality and the environmental benefits of using this material, aesthetics also played a major role in making it the material of choice.

“Sandy desert winds and a merciless sun are probably the fiercest enemies of any facade in Egypt,” Arafa admits. His response was, well, “if you can’t beat them, join them.” A local type of sandstone known in Egypt as ‘Hashma’ was custom-cut for the house. The stone’s thickness, combined with 30cm cavity walls and its natural properties helped increase the time-lag, subsequently improving thermal insulation. Aside from the functionality and the environmental benefits of using this material, aesthetics also played a major role in making it the material of choice.

“Out of many aesthetic qualities this stone possesses, overcoming monotony through reflecting nature’s daily cycle is the most significant,” Arafa explains. “This specific type of Hashma welcomes sunrise in a dark, brown-sugar colour that keeps getting lighter as the sun steals away its water content gained from dew and makes it paler throughout the day, and then dramatically catches red flames off the setting sun.”

“Out of many aesthetic qualities this stone possesses, overcoming monotony through reflecting nature’s daily cycle is the most significant,” Arafa explains. “This specific type of Hashma welcomes sunrise in a dark, brown-sugar colour that keeps getting lighter as the sun steals away its water content gained from dew and makes it paler throughout the day, and then dramatically catches red flames off the setting sun.”

New houses in Egypt often combine contrasting materials in their designs. Sometimes they don’t complement one another and other times they do. In Dar Arafa, the latter was true. Instead of using the popular but less environmentally friendly aluminium sections for the sliding windows and doors, wood was used to maintain the aesthetic rhythm established by Hashma stone.

New houses in Egypt often combine contrasting materials in their designs. Sometimes they don’t complement one another and other times they do. In Dar Arafa, the latter was true. Instead of using the popular but less environmentally friendly aluminium sections for the sliding windows and doors, wood was used to maintain the aesthetic rhythm established by Hashma stone.

Those windows and doors are double-glazed, with 21mm thickness used to maintain thermal and sound insulation. As for the balconies’ balustrades, handrails and vertical core’s protective grill, they were all made out of hollow steel sections. “The grill intends to be the skeleton of a climbing plant,” Arafa explains. “Through sensitive, studied trimming and shaving of this climber, the core gets the desired amounts of ventilation and light, while filtering noise, dust and glare.”

Those windows and doors are double-glazed, with 21mm thickness used to maintain thermal and sound insulation. As for the balconies’ balustrades, handrails and vertical core’s protective grill, they were all made out of hollow steel sections. “The grill intends to be the skeleton of a climbing plant,” Arafa explains. “Through sensitive, studied trimming and shaving of this climber, the core gets the desired amounts of ventilation and light, while filtering noise, dust and glare.”

Inside, either local Egyptian marble or dark brown high density fiberboard covers the floors. Spaces were dictated by the architecture of the building. To complement their living experience, more openings were due. “Wind-catching skylights were an inherent addition to the sustainability of Dar Arafa,” Arafa says, pointing to the openings that allow fresh New Cairo air to ventilate the top duplex and flood the double height space with daylight. Having erected the structure, completed its architecture and decorated its interiors, it was time for the architect to rest within his living space and look back at the challenges that were faced. These challenges weren’t financial or logistical, however; they were theoretical.

Inside, either local Egyptian marble or dark brown high density fiberboard covers the floors. Spaces were dictated by the architecture of the building. To complement their living experience, more openings were due. “Wind-catching skylights were an inherent addition to the sustainability of Dar Arafa,” Arafa says, pointing to the openings that allow fresh New Cairo air to ventilate the top duplex and flood the double height space with daylight. Having erected the structure, completed its architecture and decorated its interiors, it was time for the architect to rest within his living space and look back at the challenges that were faced. These challenges weren’t financial or logistical, however; they were theoretical.

“I was originally sceptical about what a limited budget would cover in relation to my demands and aspirations,” he admits. Despite this, he stayed true to the philosophical drive behind his design, one which could be found throughout Dar Arafa Architecture’s portfolio: never to make concessions regarding professional integrity. “My point of departure was rooted in a fallacy, usually promoted by mediocre engineers and contractors, that creative designs essentially have to cost more money.”

“I was told that if I insisted on having a garden that I would have to put up with a smaller floor area,” he continues. “Conventional neighbouring designs that ignored the advantage of being predecessors of Dar Arafa proved to have much more direct and indirect costs, reduced floor areas and no considerable green spaces.”

“I was told that if I insisted on having a garden that I would have to put up with a smaller floor area,” he continues. “Conventional neighbouring designs that ignored the advantage of being predecessors of Dar Arafa proved to have much more direct and indirect costs, reduced floor areas and no considerable green spaces.”

Juggling the realities that were uncovered as he made those comparisons, Arafa was filled with confidence in the design decisions which formed his home. Dar Arafa was the first project constructed in its area, as well as it being the architect’s first fully independent design and build project.

Juggling the realities that were uncovered as he made those comparisons, Arafa was filled with confidence in the design decisions which formed his home. Dar Arafa was the first project constructed in its area, as well as it being the architect’s first fully independent design and build project.

“Dar Arafa was an opportunity to establish a fresh architectural vocabulary for the newly emerging neighbourhood,” Arafa looks back. “New Cairo was a white canvas ready to bear the visions of many young architects given similar commissions. Sadly, many of these architects have fallen for meaninglessness, commercialism or simply didn’t succeed in educating their clients on what architecture in 21st century Cairo stood for.”

“The result was a generation of buildings oblivious to great lessons from the past, lacking understanding of the present and never attempting to explore the creation of a future, appearing one after the other on the horizon,” Arafa continues. “Some thought they were doing a great job replicating proportionally distorted Corinthian columns whilst others left their design sensibilities to be informed by reflective glass providers and aluminium cladding suppliers. Frustrated by clients and contractors alike, they caved in believing the status quo was immutable.”

“The result was a generation of buildings oblivious to great lessons from the past, lacking understanding of the present and never attempting to explore the creation of a future, appearing one after the other on the horizon,” Arafa continues. “Some thought they were doing a great job replicating proportionally distorted Corinthian columns whilst others left their design sensibilities to be informed by reflective glass providers and aluminium cladding suppliers. Frustrated by clients and contractors alike, they caved in believing the status quo was immutable.”

Dar Arafa, along with its architect owner, fought hard to break the cycle of self-victimisation and brought hope to fellow young architects by showing that it is possible to build to their aspirations and highlighting the achievability of environmental strategies and techniques that are learnt in theory and academia.

Dar Arafa, along with its architect owner, fought hard to break the cycle of self-victimisation and brought hope to fellow young architects by showing that it is possible to build to their aspirations and highlighting the achievability of environmental strategies and techniques that are learnt in theory and academia.

Acting not only as the start of Dar Arafa Architecture’s string of influential designs but also its ethos, the house was built by a young generation of craftsmen, designed and constructed mainly by those under 30 years old. “It benefited from their fresh minds and muscle, with an unconventional building for their portfolios in return,” Arafa expresses.

Acting not only as the start of Dar Arafa Architecture’s string of influential designs but also its ethos, the house was built by a young generation of craftsmen, designed and constructed mainly by those under 30 years old. “It benefited from their fresh minds and muscle, with an unconventional building for their portfolios in return,” Arafa expresses.

After its completion, Dar Arafa hosted field trips for those interested in exploring design, non-conventional materials, architectural politics and environmental necessities. Today, the owners live in the duplex, experiencing both extremes of cold winter and hot summer months as they witness the success of the cavity wall and its thermal insulation. Meanwhile, one of the ‘branches’ acts as the office space for the architectural firm.

After its completion, Dar Arafa hosted field trips for those interested in exploring design, non-conventional materials, architectural politics and environmental necessities. Today, the owners live in the duplex, experiencing both extremes of cold winter and hot summer months as they witness the success of the cavity wall and its thermal insulation. Meanwhile, one of the ‘branches’ acts as the office space for the architectural firm.

Photography Credit: Essam Arafa

Photography Credit: Essam Arafa

- Previous Article سندباد الورد أضحي سلطاناً: مراجعة لألبوم شب جديد والناظر 'سلطان'

- Next Article CBE Issues Regulations for Licensing of Digital Banks