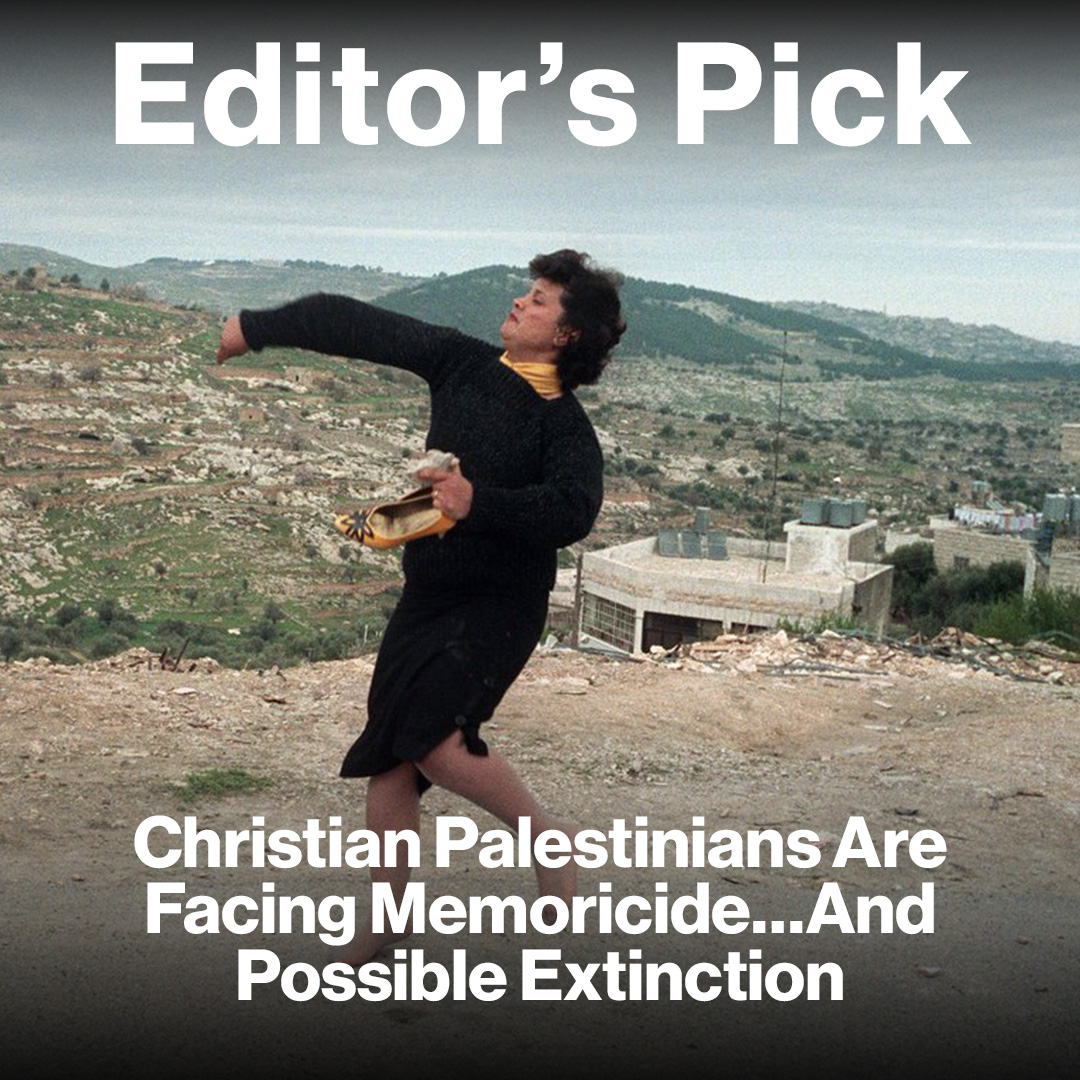

A Century of Modern Egyptian Art at Zamalek’s Picasso Gallery

The father-daughter duo who run Zamalek’s celebrated Picasso Gallery take us on a journey through Egypt’s modern art history.

(Ibrahim 'Picasso' Abdel Rahman at the grand opening of the Picasso Gallery in 1996)

In one of the side streets off Zamalek’s main thoroughfares on a calm Thursday afternoon, Nagwa Ibrahim accompanied me to the private showroom of the Picasso Gallery. Elegant and glamorous, Ibrahim is the manager at Picasso and often curates exhibitions there. Whetting my appetite for the priceless works of modern Egyptian art housed in the private showroom, Ibrahim began telling tales of her childhood spent around some of the greatest doyens of Egypt’s fine arts milieu.

“As a child, I would visit the home of Hussein Bicar with my father. They were dear friends, and as he was our neighbour in Zamalek, we would spend a lot of time with him at home,” shared Nagwa Ibrahim. “He was an artist in the genuine sense of the word- creating constantly through feeling.”

(Abdel Rahman with Pope Shenouda III at the Picasso Gallery's opening in 1996.)

(Abdel Rahman with Pope Shenouda III at the Picasso Gallery's opening in 1996.)

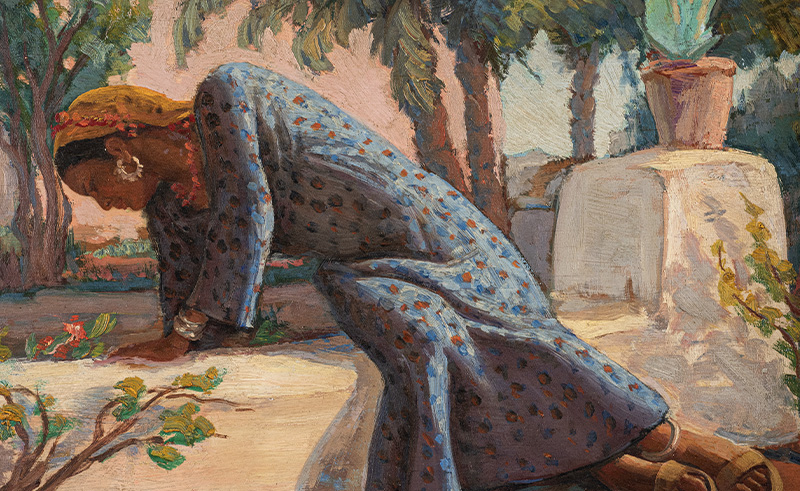

Stepping into the private showroom, housed in a grand, old apartment, one’s senses are immediately overwhelmed. Here, I saw a painting by the legendary Egyptian surrealist Inji Aflatoun of fellaheen agriculturalists collecting ripe oranges. Besides it hung pieces mesmerizingly portraying scenes of a performance of the Egyptian ballet by Alexandrian-born master, Seif Wanly. Room after room, one is entangled in the immense history and legacy left behind by Egypt’s modern artists, reflecting the moods of the country through the moments which shaped it, and were observed and documented in rich hues. From the decadence and cosmopolitanism of the Royalist era, to the nationalist and class conscious spirit of the socialist Republic, to the Cairene and Alexandrian cultural establishment’s grappling with the Egyptian role in Palestine, to the monumental moments which created modern Egypt - the private showroom is a kaleidoscope and archive of life, of culture and of the exquisite mastery of the hands of Egyptian fine artists.

As we were settling down to interview Ibrahim further on the history and legacy of the Picasso Gallery, we were enticed by a proposal. “My father, Mr. Ibrahim, is the founder of Picasso. He’s around and he loves telling stories,” proposes Nagwa Ibrahim with a glint of pride. Moments later, a debonair and dandy older gentleman joins us for a sit down, and takes us on a trip through the last half-century of Cairo’s artistic community.

(Abdel Rahman formally inaugurating the gallery with a number of distinguished dignitaries.)

(Abdel Rahman formally inaugurating the gallery with a number of distinguished dignitaries.)

Ibrahim Abdel Rahman - also known as Ibrahim Picasso, a fond moniker given to him by Hussein Bicar - is dressed immaculately in chinos and a polo shirt, an eager glimmer in his eyes as we begin asking him about his memories of the artists around whom he spent his life. “I entered the world of Cairo’s fine arts community through my apprenticeship as a frame-maker. I worked with a certain Jewish gentleman, who would make frames for all the big names,” shares Abdel Rahman. “The older artists took a liking to me, and we became dear friends. I wasn’t just the boy who brought them their frames.” Recalling his beginnings of association with the arts, Abdel Rahman is visibly moved, entranced in his memories of yesteryear. “In 1967, during the flight of the Jewish and foreign communities from Egypt, the gentleman I apprenticed with left the country, and left behind the list of clients who I would now be solely responsible for.”

His beginnings as a frame-maker for the masters brought to Abdel Rahman a realisation of his life’s calling of serving the arts. “I would never charge much for the frames, even though it could have been a way to make a fortune. People don’t realise that even though these artists who were my clients were world-renowned, they were also just artists, and artists in their living days tend not to make much money. No, it was never money making. Our artistic community in Cairo was dedicated to serving the arts, it was not an abstract relationship.”

(Abdel Rahman formally inaugurating the gallery with a number of distinguished dignitaries.)

(Abdel Rahman formally inaugurating the gallery with a number of distinguished dignitaries.)

Behind Abdel Rahman’s chair were pieces by Inji Aflatoun and Tahia Halim, another leading figure of Egyptian modern art, and a painter at the forefront of Egyptian expressionism. Apart from being pioneers in the Surrealist and Expressionist Movements in the country respectively, these women were personal and dear friends of Abdel Rahman.

“I would always be between Aflatoun’s home in Cairo and her countryside estate in Banha. She would call me if she needed a canvas or something she had forgotten at her home in Cairo and I would take a drive to the country to visit her on a Sunday. Sundays for me were either days spent with Inji or with Tahia,” recalls Abdel Rahman about the legendary painters.

Aflatoun, although of aristocratic lineage, dedicated her life to the Egyptian Communist movement, and viewed her role as an artist crucial in centering the rural and working class essence of the country. To that end, she spent most of her time in the countryside amongst the peasantry, painting and documenting their day-to-day lives.

“Like today, Palestine was a central cause amongst the cultured classes. Aflatoun was wholly dedicated to it,” Abdel Rahman says. “When I was younger, and found myself in a difficult position once, Aflatoun gave me 500 Egyptian Pounds to help me. She never expected a repayment, that was not in her nature. When she died, I recalled this immensely kind gesture from her, and donated the equivalent figure to charities associated with the Palestinian cause in the name of Inji Aflatoun.”

(The Picasso Gallery on Hassan Assem Street, Zamalek.)

(The Picasso Gallery on Hassan Assem Street, Zamalek.)

The Picasso Gallery was opened in 1996, and is what Abdel Rahman calls “his great service to the arts.” Cairo then was lacking independent places for artists to showcase their works, and Abdel Rahman sought to remedy that. “The few exhibition halls in the city were government-run, and naturally this created a barrier to the many talented creatives of Cairo to exhibit their works,” says Abdel Rahman. The gallery was not only created as an exhibition hall, but also as a space, a collecting point, for the old doyens to easily and comfortably interact with the rising generations of creatives. “At opening the gallery, I wanted to involve new generations who didn’t have an artistic home to develop in, and to bring them here, and surround them to associate with and be mentored by the greats.”

The greats for their part were greatly enthused by Picasso’s ethos. “Just before our grand opening, around 65 of the most renowned Egyptian artists of the day gifted the gallery with some of their most important works. They didn’t want payment in turn, this was an act on their part of service to the city’s artistic establishment.” A gift in perpetuas, this story is a reflection of the temperament of the duty deeply felt by the pioneers of modern Egyptian art in creating a community of like-minded creatives in the city.

(The Picasso Gallery on Hassan Assem Street, Zamalek.)

(The Picasso Gallery on Hassan Assem Street, Zamalek.)

Abdel Rahman holds no angst for the changing tastes of contemporary Egyptian art. Instead, he views it with admiration and respect. “During Nasser’s period, there was a sense of duty felt by the country’s intelligentsia towards reflecting the moment that Egypt found itself in. ‘El Za’im w El Ta’mim El Kanal’ by Hamed Ewais, for example, is a reflection of the immense pride and connection that the country’s citizens experienced when Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal in 1956,” says Abdel Rahman. “Now too, the youth who have invested their lives in the arts are reflecting the moods of their generation, and that is necessary and important.”

Nagwa Ibrahim, the youthful manager of Picasso who had been looking on as we interviewed her father, gave her perspective of the differences in generation. “The younger generations naturally have a different view than the older. As important as the old masters and pioneers are, the voice of the emerging generations too need a platform from which to exhibit their art. Through this ideal, which is the founding ethos of Picasso, to propel and showcase the immensity of Egyptian art to the world, we established a second hall to exhibit more contemporary artists.”

Ibrahim’s love for the arts led her to train professionally as an art curator, and she is committed to using her skills to spotlight the vibrancy of Egypt’s arts. “Our artists are amazing and aplenty, and all the world should experience the exuberance of the country’s emerging artists,” shares Nagwa Ibrahim.

The Picasso Gallery today is as it was at its inception, a gathering place for the city’s cultural milieu. The legacy left behind by the virtuosos of days gone by is physically preserved in the halls situated on Zamalek’s Hassan Assem Street. It remains a space of community and stillness, inviting lovers and students of history and art, painting novices and aged collectors alike, to observe the hallowed history of a century of Egypt’s evolution. Abdel Rahman comments sagely before he leaves, “Always the ability to create art comes from one who observes well, and as life changes through generations, so does the observation of life, creating new ways of expression.”

Trending This Week

-

Apr 23, 2024